Singleton Design Pattern in C++

1. Uses of Singleton

A singleton design pattern ensures that only one instance of a class exists and that the instance is initialized only once. The instance is accessed globally.

The singleton relies on a mechanism called lazy initialization. This refers to the process of delaying the allocation of memory or resources until they are explicitly needed as opposed to pre-allocating them when the program starts.

Additionally, a singeton must often be prepared to manage concurrent access to a shared resource. To summarise, it must satisfy the following requirements:

- Only one singleton object can exist.

- Centrally manage access requests to a shared resource (in a many-to-one fashion).

- (Optional) Be able to manage concurrent access to the shared resource.

Why use it? Let’s say we have a system where multiple components write to the same array (e.g. an image).

- Single initialization. It guarantee that the array is initialized exactly once and that all points share the same instnace.

- Controlled access. The singleton instance is fully responsible for accessing the array and can implement logic to handle concurrent writes (e.g. a mutex).

- Centralized management. The singleton routes all array writes and it can enforce rules to access it.

Singleton is a controversial pattern and it’s considered by many an anti-pattern. However, it’s worth understanding its mechanism and it can still come in handy if designed with care. Let’s have a deep dive.

2. Basic Concepts

2.1. Private Constructor

Making a constructor private overrides the default public constructor.

Private constructors are not called when an instance is created.

By making a constructor, e.g. private: DummyClass(int v) private, there can be no

public constructor public: DummyClass(int v), therefore executing DummyClass(42);

would throw an error.

The code below does not compile as the constructor is unable to be called.

Listing 1. Attempting to call a private constructor.

#include <iostream>

class DummyClass {

private:

int data;

// private constructor can't be called upon creation

DummyClass(int v) : value(v) {}

};

int main() {

DummyClass obj(111); // ERROR!

return 0;

}

So what’s the use of it and how can this compile?

2.2. Static Methods

To be able to call the static constructor, we’d need an instance method. However,

an instance cannot be created, so the trick is to use a class method instead,

i.e. a static method bound to the class itself. This can be invoked as MyClass::createInstance(5)

and it calls in turn the private constructor. Only this way can an instance be created.

Listing 2. Calling a private constructor via static method.

#include <iostream>

class DummyClass {

private:

int data_;

DummyClass(int v) : data_(v) {}

public:

// Static method to create an instance -

// bound to the class, not an instance

static DummyClass CreateInstance(int v) { return DummyClass(v); }

void Display() const { std::cout << "Data: " << data_ << std::endl; }

};

int main() {

DummyClass obj1 = DummyClass::CreateInstance(42); // OK

DummyClass obj2 = DummyClass::CreateInstance(43); // OK

obj1.Display();

obj2.Display();

return 0;

}

This will compile normally and as expected, it yields:

Data: 42

Data: 43

To summarize, the private constructor paired with a static creation method does not limit the number of instances of a class we can have, but routes the creation via a static class method.

2.3. Private Destructor

Much like its counterpart private constructor, private constructor is also used to control the lifecycle of an instance. Private destructors are typically used when other entities are responsible for the lifetime of the one with a private destructor. Making a destructor private makes the compiler unable to automatically call it when the instance gets destroyed. So if a private destructor is not called manually upon the end of its lifecycle, we risk introducing memory leaks.

A consequence of that is that stack-allocated objects cannot have a private destructor.

Just like private constructors, private destructors are bound to the class, i.e. defined

within the class itself as static methods. That said, let’s extend DummyClass to implement

one.

Listing 3. A private constructor that allocates memory needs private destructor.

#include <iostream>

class DummyClass {

private:

int data_;

DummyClass(int v) : data_(v) {}

~DummyClass() {

std::cout << "Destructor called for data: " << data_ << std::endl;

}

public:

// Create a heap instance to manually delete it later in the d/tor

static DummyClass* CreateHeapInstance(int v) {

return new DummyClass(v);

}

// To explicitly deallocate each instance

static void DestroyHeapInstance(DummyClass* instance) {

delete instance;

}

void Display() const { std::cout << "Data: " << data_ << std::endl; }

};

int main() {

DummyClass* obj1 = DummyClass::CreateHeapInstance(42);

obj1->Display();

DummyClass* obj2 = DummyClass::CreateHeapInstance(43);

obj2->Display();

DummyClass::DestroyHeapInstance(obj1);

DummyClass::DestroyHeapInstance(obj2);

return 0;

}

This prints:

Data: 42

Data: 43

Destructor called for data: 42

Destructor called for data: 43

2.4. Static Instance Bound To The Class

A static variable in a class is bound to the class itself and cannot be accessed externally. It’s initialized by the class. Its lifetime spans the entire program and it is initialized only once, no matter how many instances of the class are created.

Below is a simple example that uses this technique to count the number of instances created.

Listing 4. A static variable bound to the class.

#include <iostream>

class Counter {

private:

// Counts how many instances of the class we have

static int instanceCount;

public:

Counter() { instanceCount++; } // Increment on creation

~Counter() { instanceCount--; } // Decrement on destruction

// Class-bound method

static int GetInstanceCount() { return instanceCount; }

};

// Initialize it outside the class

int Counter::instanceCount = 0;

int main() {

Counter obj1;

Counter obj2;

std::cout << "Number of instances: " << Counter::GetInstanceCount()

<< std::endl;

{

Counter obj3;

std::cout << "Number of instances: " << Counter::GetInstanceCount()

<< std::endl;

}

std::cout << "Number of instances: " << Counter::GetInstanceCount()

<< std::endl;

return 0;

}

It prints:

Number of instances: 2

Number of instances: 3

Number of instances: 2

2.5. Lazy Initialization

The last concept to be comfortable with before moving on to implement the singleton is lazy initialization (sometimes called deferred allocation). Lazy initialization is just a term for delaying the allocation of an object until it’s explicitly needed.

I will deomostrate how this works in a scenario where we have a log file that is meant to

be written by multiple access pointer (in this case instances). I will work with C-style FILE

pointers to demonstrate the resource allocation better. First, let’s make a simple wrapper around

the C-style FILE* to provide it with a new method, a deleter and a Write method.

Listing 5. Using private constructors and lazy initialization to implement a file writer.

#include <cstdio>

#include <memory>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

/**

* Wrapper around C-style FILE pointer in order to provide FILE* a new method,

* a destructor, and a Write method.

*/

class File {

public:

File() = delete;

// explicit to prevent unwanted implicit conversion std::string -> File

explicit File(const std::string &filename) {

file_ = std::fopen(filename.c_str(), "w");

if (!file_)

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: Failed to open file!");

}

~File() {

if (file_)

fclose(file_);

};

void Write(const std::string &data) {

if (file_)

std::fputs(data.c_str(), file_);

}

private:

FILE *file_;

};

/**

* Manages each file, allowing multiple instances to write to the same file

*/

class FileWriter {

static std::unique_ptr<File> logfile;

public:

FileWriter() = delete;

~FileWriter() { /* not needed - everything managed automatically */ }

FileWriter(const std::string &filename) {

if (FileWriter::logfile == nullptr) {

// allocate only when needed

FileWriter::logfile = std::make_unique<File>(filename);

}

}

void Write(const std::string &data) {

if (FileWriter::logfile)

FileWriter::logfile->Write(data);

else

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: File manager not initialized!");

}

};

// initialize to nullptr but don't allocate yet

std::unique_ptr<File> FileWriter::logfile = nullptr;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

std::string fname = "output.txt";

FileWriter writer1(fname);

FileWriter writer2(fname);

writer1.Write("Input logs from writer1.\n");

writer2.Write("Input logs from writer2.\n");

writer1.Write("Bye bye from writer1!\n");

writer2.Write("Bye bye from writer2!\n");

return 0;

}

I use the

explicit keyword in the constructor to prevent situtations the constructor from being used in

implicit conversions. Imagine the following scenario. Without an explicit constructor, 42 would

be converted to Cls(42).

class Cls {

public:

Cls(int value) {}

};

void func(Cls ex) {}

int main() {

func(42); // Implicitly converts `42` into an `Foo` object

// with an explicit c/tor, this would throw an error

return 0;

}

Now let’s get back to designing a FileWriter class that uses lazy initialization.

All instance should write to a FILE* via the global logfile_. The later is initialized

to nullptr but not allocated. It is only allocated when we want to create an instance to

FileWriter and allocated exactly once. The FileWriter destructor doesn’t need to do anything

as FileWriter is a static unique pointer to File. The file clears clears its resources itself

by calling fclose.

#include <cstdio>

#include <memory>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

/**

* Wrapper around C-style FILE pointer in order to provide FILE* a new method,

* a destructor, and a Write method.

*/

class File {

public:

File() = delete;

// explicit to prevent unwanted implicit conversion std::string -> File

explicit File(const std::string &filename) {

file_ = std::fopen(filename.c_str(), "w");

if (!file_)

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: Failed to open file!");

}

~File() {

if (file_)

fclose(file_);

};

void Write(const std::string &data) {

if (file_)

std::fputs(data.c_str(), file_);

}

private:

FILE *file_;

};

/**

* Manages each file, allowing multiple instances to write to the same file

*/

class FileWriter {

static std::unique_ptr<File> logfile;

public:

FileWriter() = delete;

~FileWriter() { /* not needed - everything managed automatically */ }

FileWriter(const std::string &filename) {

if (FileWriter::logfile == nullptr) {

// allocate only when needed

FileWriter::logfile = std::make_unique<File>(filename);

}

}

void Write(const std::string &data) {

if (FileWriter::logfile)

FileWriter::logfile->Write(data);

else

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: File manager not initialized!");

}

};

// initialize to nullptr but don't allocate yet

std::unique_ptr<File> FileWriter::logfile = nullptr;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

std::string fname = "output.txt";

FileWriter writer1(fname);

FileWriter writer2(fname);

writer1.Write("Input logs from writer1.\n");

writer2.Write("Input logs from writer2.\n");

writer1.Write("Bye bye from writer1!\n");

writer2.Write("Bye bye from writer2!\n");

return 0;

}

This prints:

Input logs from writer1.

Input logs from writer2.

Bye bye from writer1!

Bye bye from writer2!

2.6 Lazy Initialization with Mutexes

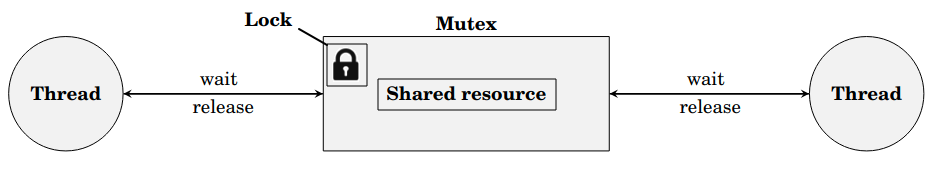

If access points from multiple threads write to logfile, they may end up writing

data at the same time, corrupting each other’s data. To do this, we can add a mutex in FileWriter’s Write

method that safeguards what’s written into the file, by locking access before line:

FileWriter::logfile->Write(data);

and unlocking it afterwards. The mutex (mtx) has the same lifecycle as logfile, i.e. it’s statically bound

to the FileWriter class. The mutex can either lock (to protect the file from being writte) or unlock (to allow

it to be written).

It’s often easy to forget unlocking a mutex after using it. C++ addresses this issues via lock guard (std::lock_guard).

The lock guard is an entity that works with a mutex. It locks it when it’s defined and unlocks its automatically when it goes

out of scope. Therefore to lock the shared resources,

all that’s needed is to call an the lock guard on our mutex:

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mtx);

To get some intuition, it’s easy to remember the analogy of a mutex being the key to a private room (the room being the shared resources). For a person (thread) to enter, they need to take the key. A lock guard would then be analogous to an automatic lock.

The code including a mutex to protect writing to logfile is listed below.

Listing 6. A file writer with a mutex to protect the shared resource from concurrent writes.

#include <cstdio>

#include <memory>

#include <mutex>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

#include <thread>

/**

* Wrapper around C-style FILE pointer in order to provide FILE* a new method,

* a destructor, and a Write method.

*/

class File {

public:

File() = delete;

// explicit to prevent unwanted implicit conversion std::string -> File

explicit File(const std::string &filename) {

file_ = std::fopen(filename.c_str(), "w");

if (!file_)

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: Failed to open file!");

}

~File() {

if (file_)

fclose(file_);

};

void Write(const std::string &data) {

if (file_)

std::fputs(data.c_str(), file_);

}

private:

FILE *file_;

};

#include <iostream>

void CheckMutexState(std::mutex mtx) {

if (mtx.try_lock()) {

std::cout << "Mutex is not locked.\n";

mtx.unlock();

} else {

std::cout << "Mutex is already locked.\n";

}

}

/**

* Manages each file, allowing multiple instances to write to the same file

*/

class FileWriter {

static std::unique_ptr<File> logfile;

static std::mutex mtx;

public:

FileWriter() = delete;

~FileWriter() { /* not needed - everything managed automatically */ }

FileWriter(const std::string &filename) {

if (FileWriter::logfile == nullptr) {

// allocate only when needed

FileWriter::logfile = std::make_unique<File>(filename);

}

}

void Write(const std::string &data) {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mtx);

if (FileWriter::logfile)

FileWriter::logfile->Write(data);

else

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: File manager not initialized!");

}

};

// initialize to nullptr but don't allocate yet

std::unique_ptr<File> FileWriter::logfile = nullptr;

std::mutex FileWriter::mtx;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

std::string fname = "output.txt";

FileWriter writer(fname);

std::thread t1(&FileWriter::Write, &writer, "Write #1\n");

std::thread t2(&FileWriter::Write, &writer, "Write #2\n");

std::thread t3(&FileWriter::Write, &writer, "Write #3\n");

t1.join();

t2.join();

t3.join();

return 0;

}

The output does not necessarily appear in the order defined by the threads in the program, .e.g it cal be:

Write #3

Write #2

Write #1

2.7 Deleting the Assignment and Copy Constructors

One of the required properties of a singleton is that there can be only one instance of it. Therefore singletons cannot be copied (e.g. initialized from one another) or assigned to one another.

This is done by deleting the copy constructor and assignment operator, so

copying or assugning the FileWrapper would result in an error:

FileWriter(const FileWriter &) = delete;

FileWriter &operator=(const FileWriter &) = delete;

At this point, the singleton is almost complete but let’s take a look at how the copy and assignment consstructors are called.

2.7.1. More about Copy Constructor Vs Assignment Operator

A copy constructor is used to initialize a previously uninitialized object from some other object’s data. It’s therefore called in the following cases:

- When an object is initialized from another object of the same type.

- When an object is passed by value to a function.

- Depending on the compiler’s NRVO (Named Return Value Optimization), it MAY be called when an object is returned by value from a function.

The assignment operator is called when replacing the data of a previously initialized object with some other object’s data.

Let’s see them in action.

Listing 7. Quiz on copy constructor vs assignment operator.

#include <iostream>

class Dummy {

public:

Dummy() { std::cout << "Default constructor" << std::endl; }

Dummy(const Dummy &) { std::cout << "Copy constructor" << std::endl; }

Dummy &operator=(const Dummy &) {

std::cout << "Copy assignment operator" << std::endl;

return *this;

}

};

void foo(Dummy dummy) {}

Dummy bar() { return Dummy(); }

Dummy foobar() {

Dummy d;

return d;

}

int main() {

std::cout << "(1): ";

Dummy a;

std::cout << "(2): ";

Dummy b = a;

std::cout << "(3): ";

foo(a);

std::cout << "(4): ";

bar();

std::cout << "(5): ";

foobar();

std::cout << "(6): ";

Dummy c = foobar();

std::cout << "(7): ";

b = a;

return 0;

}

This prints:

(1): Default constructor

(2): Copy constructor

(3): Copy constructor

(4): Default constructor

(5): Default constructor

(6): Default constructor

(7): Copy assignment operator

So when b is uninitialized, the copy contructor is called, otherwise it’s the copy assignment

operator.

3. Implementing the Singleton

FileWriter needs a few more modifications based on the techniques we explored earlier

to be converted into a singleton, namely:

- The current code allows one

Fileinstance but allows multipleFileWriterinstances. Singleton strictly allows one instance ofFileWriter. FileWriterneeds aGetInstancemethod to lazily instantiate and reuse the same instance.

To tackle (1) and (2) we add a static GetInstance method bound to the FileWriter class.

FileWriter’s constructor remains private, as earlier.

- FileWriter(const std::string &filename) {

- if (FileWriter::logfile == nullptr) {

- // allocate only when needed

- FileWriter::logfile = std::make_unique<File>(filename);

+ static FileWriter &GetInstance(const std::string &filename = "") {

+ static FileWriter instance(filename);

+ // extra error chiecking omitted in diff

+ return instance;

+ }

To fully satisfy (1), FileWriter must not be copied or assigned, which is achieved by deleting the copy constructor and assignment operator as discussed earlier:

+ // Delete copy constructor and assignment operator to enforce Singleton

+ FileWriter(const FileWriter &) = delete;

+ FileWriter &operator=(const FileWriter &) = delete;

Some error checking is also added. In the main, apart from writing to a log file from

3 threads, we additionally refer to the FileWriter instance in another function and write

to the log file from there. This works and writes to the same output as the instance is unique.

Finally, notice that in main we always create a reference to FileWriter as the instance is unique and static:

int main() {

// ...

FileWriter &writer = FileWriter::GetInstance();

}

Below is the final code the logger singleton.

Listing 8. Full code for a logger singleton.

#include <cstdio>

#include <memory>

#include <mutex>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

#include <thread>

/**

* Wrapper around C-style FILE pointer in order to provide FILE* a new method,

* a destructor, and a Write method.

*/

class File {

public:

File() = delete;

explicit File(const std::string &filename) {

file_ = std::fopen(filename.c_str(), "w");

if (!file_)

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: Failed to open file!");

}

~File() {

if (file_)

fclose(file_);

}

void Write(const std::string &data) {

if (file_)

std::fputs(data.c_str(), file_);

}

private:

FILE *file_;

};

/**

* FileWriter Singleton: ensures only one instance manages file writing.

*/

class FileWriter {

public:

static FileWriter &GetInstance(const std::string &filename = "log.txt") {

static FileWriter instance(filename);

if (!filename.empty() && filename != instance.filename_)

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: Singleton instance already initialized "

"with a different filename: " +

instance.filename_);

return instance;

}

// Delete copy constructor and assignment operator to enforce unique instance

FileWriter(const FileWriter &) = delete;

FileWriter &operator=(const FileWriter &) = delete;

void Write(const std::string &data) {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mtx_);

if (logfile_)

logfile_->Write(data);

else

throw std::runtime_error(

"ERROR: FileWriter must first open a file to write to!");

}

private:

std::unique_ptr<File> logfile_;

std::mutex mtx_;

std::string filename_;

explicit FileWriter(const std::string &filename) {

if (!filename.empty()) {

logfile_ = std::make_unique<File>(filename);

filename_ = filename; // so we don't write to another file

} else {

throw std::runtime_error("ERROR: Filename cannot be empty!");

}

}

};

void foo() {

FileWriter &writer = FileWriter::GetInstance();

writer.Write("Write from another function\n");

}

int main() {

FileWriter &writer = FileWriter::GetInstance();

std::thread t1(&FileWriter::Write, &writer, "Write #1\n");

std::thread t2(&FileWriter::Write, &writer, "Write #2\n");

std::thread t3(&FileWriter::Write, &writer, "Write #3\n");

t1.join();

t2.join();

t3.join();

foo();

// Attempt to reuse the Singleton with a different filename

// - uncommenting the next line will throw an exception

// FileWriter &writer2 = FileWriter::GetInstance("another_log_file.txt");

return 0;

}

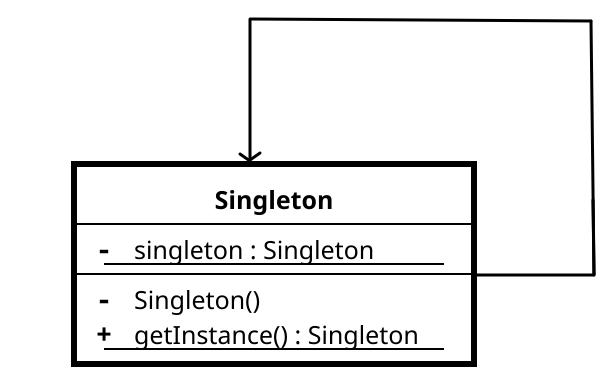

To make it easier to remember, here’s the UML diagram of a typical singleton (credits wikipedia).

4. Summary

| Aspect | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Global Access | Provides controlled global access to a shared resource. | Can introduce implicit coupling between classes. |

| Encapsulation | Wraps around the shared state, avoiding scattered global variables. | Introduces global state, which may complicate debugging. |

| Initialization | With lazy initialization, it saves resources if the instance isn’t always needed. | N/A. |

| Thread Safety | Easy to make thread-safe, e.g. with a mutex. | The usual multithreading drawbacks like race conditions. |

| Resource Management | Centralizes resource management, ideal for loggers, many-to-one writes, or database connections. | Reduces flexibility since only one instance is allowed, complicates testing. |